Originally published on The Huffington Post on 3/27/2016.

To fit into male-dominated spaces, women are told to fix a lot of things: stop using “sorry” and “just” in emails, avoid vocal fry and upspeak, and “watch your tone” at all times.

But more than anything else, women are told that it’s a lack of confidence that’s really holding us back. If only we could get over imposter syndrome, and internalize our successes instead of feeling like serially lucky frauds, we’d be unstoppable.

Too bad it doesn’t work like that. There is a very real external bias against women’s competence, and nobody gets around it by being more confident. In fact, as we see through the experiences of Hillary Clinton and Melissa Harris-Perry, being more confident can result in harsh pushback when you’re pursuing leadership positions within male-dominated environments. Because how dare you.

While we’re so busy focusing on what women should and should not do, there’s a big problem going undiagnosed: entitlement syndrome. The opposite of imposter syndrome, entitlement syndrome is the problem of overconfident mediocre white men. After I break down competence bias, I’ll get into what entitlement syndrome looks like, and what some concrete solutions might be.

What competence bias looks like

Women are assumed to be less competent, less trustworthy, and are held to a higher standard overall than men. There’s a much greater chance that their work will be ignored, discounted, trivialized, devalued, or otherwise not taken seriously. The more success a woman experiences, the stronger these external forces become. They’re also magnified by intersecting biases, like racism and homophobia.

It’s easy to see how imposter syndrome is a rational response to competence bias. Why would you think you’re competent, if nobody else does?

Competence bias starts early. Girls learn that they’ll be held to higher standards physically, intellectually, and behaviorally than boys. While boys are raised to exaggerate their skills, take risks, fall down and pick themselves back up, girls are taught to think things through and second-guess, avoid risk and failure, and not raise their hand unless they’re sure they have the right answer. Lastly, girls absorb from the media that their real value lies in their appearance, at the same time that boys absorb the message that girls are not to be trusted.

It’s not simple to undo such deeply held, unconscious biases. Telling women to counteract the entirety of competence bias by being more confident is like telling one of Cinderella’s stepsisters to squeeze her foot harder into the glass slipper. It’s never going to work. The structure itself has to shift, which is going to take work by both women and men (I’ll get into this more later).

However, self-confidence in the face of oppression is extremely disruptive to power structures. Audre Lorde called self-love “an act of political warfare“, and Maya Angelou wrote about its power to upset and offend oppressors. When a woman is confident instead of self-doubting, it means she’s no longer playing by the rules. It triggers intense pushback, as we’ll see in the stories of Hillary Clinton and Melissa Harris-Perry.

Hillary Clinton’s experience

Hillary Clinton’s list of accomplishments puts her in the top echelons of high achieving women. Not only was she the first female partner at a major law firm, but she went on to serve as First Lady of Arkansas, First Lady of the United States, US Senator from New York, and Secretary of State. She ran for president in 2008, and now, eight years later, she’s doing it again.

According to Nate Silver’s analysis, Hillary Clinton has earned consistently high approval ratings in each of her government positions. In 2013, as Secretary of State, her 69% approval rating made her the most popular politician in the country. But Silver also found that the moment Clinton hits the campaign trail for any kind of political office, her approval rating crashes. Why? Writer Sady Doyle sums it up like this:

“Campaigning is not succeeding. It’s asking for success, and for power. To campaign is to publicly claim that you are better than the others (usually white men) who want the same job, and that a whole lot of people should work to place you in a more powerful position. In other words, campaigning is a transgressive act for women… Women who put themselves forward in the same assertive, confident style as men are routinely found pushy, “bitchy,” or unlikable, and professionally penalized for that, too.”

This is a paradox. The public has tremendous respect for Hillary Clinton as long as she has her head down and is working hard. But the moment she asks credit, acknowledgment, and a promotion, that admiration turns to vitriol. By confidently asking for what she wants, and stating why she deserves it, Clinton brings her competence into question.

Sound familiar? A lot of women have experienced sexism in their workplace performance reviews that closely parallels Clinton’s experience. After all, what is a political campaign but a huge, public performance review? Reviews are a minefield for high-achieving women. Several studies have come out recently confirming that women displaying confident, assertive behavior at work are often labeled “abrasive”, “bossy”, “strident”, “emotional” and “irrational” in their performance reviews. Fun fact: the word “abrasive” literally never appears in men’s performance reviews. What does it mean to be called “abrasive”? Without a doubt, it means “stay in your lane.” All of these forms of pushback work together to undercut a woman’s perceived competence in the workplace.

Hillary Clinton has been not-so-subtly told to stay in her lane in all kinds of different ways that undercut her competence. She was told she has a “loud, annoying, nagging wife” voice, called out for appearing without makeup, and criticized for her pantsuits. She was slammed for not showing authentic emotion, but then when her voice broke during a speech, it was widely reported as “weeping” and her ability to hold it together enough to lead was called into question. Media Matters has compiled a full list of sexist media reports from 2007-2008, organized by category (there are fourteen). A word of warning: it’s overwhelming. Even if you don’t like Hillary Clinton at all, please look at this list. (And if you need something to laugh about afterwards to bring you back up – I did – here’s the Clinton-Palin SNL skit.)

Sexist attacks on Hillary Clinton’s competence in the 2015-2016 primary season have been more subtle, but they’re still there. This time around, we’re seeing a huge focus on “trust”, which is important to recognize as a very loaded word from a gender perspective. Let me clarify that it is a valid criticism to say “I don’t trust Clinton because she has a record of [insert specific political action].” It’s not a valid criticism to imply that she just “seems” untrustworthy, or lacks authenticity and “realness” as a person. This kind of criticism essentially calls her an imposter.

Clinton’s opponent in the Democratic race, Bernie Sanders, is widely praised for being trustworthy and authentic. When arguments for Bernie Sanders being trustworthy are based on his congressional record, writings, and speeches, that’s not sexist. That’s just a regular opinion, and an important part of the political process. But when we see a recurring emphasis on Bernie’s sense of authenticity based the fact that he doesn’t care about how he looks, prefers not to brush his hair, and makes faces during debates, that is sexist. People say it’s just “Bernie being Bernie” and that he’s “bucking the traditional image of a political candidate” but it’s important to take a closer look. We find a strikingly similar example in Republican candidate Donald Trump – famous for his comb-over and spray tan – who is known for “showing real emotion” and being “not afraid to make himself look really ugly.”

Both Sanders and Trump are praised for an image that no female candidate is currently allowed to cultivate. Show me a female candidate who can throw on an ill-fitting suit, not brush her hair, and scowl and wag her finger at her opponent during a debate. The media would have a field day, not a love-fest.

The attacks on Clinton’s competence go beyond appearance. This widely-circulated meme is one example:

While the subject matter is often silly, ranging from Harry Potter to Star Wars, Bernie’s responses are crafted to demonstrate a thorough understanding of each issue. He just “gets it.” Hillary’s responses are instead designed to demonstrate enthusiastic cluelessness from a poser (imposter) spouting a totally superficial answer she thinks the crowd will like. It’s pretty close to framing her as a bimbo.

Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump have the privilege of existing in a wide lane when it comes to appearance and behavior. Not only are they assumed to be competent, and automatically praised instead of punished for the act of asking for power – but they’re encouraged to be their passionately scowling, unfashionable selves, and people love them for it.

Hillary Clinton’s lane is narrow. Not only is she a woman asking for power (an automatic transgression), but she is required to prove her competence over and over. She wins no authenticity or trustworthiness points for deviating from perfection in appearance or behavior. Sure, she can “be herself” – but the cost is that her actions will be effectively run through a de-credibility translator. Tears become hysteria. Laughing is called cackling. Frowning is a sign of mood swings. If she tries to avoid showing any emotion to avoid this kind of judgment altogether, she’s called a robot. It’s a no-win situation.

Let’s move on to MHP’s story.

Melissa Harris-Perry’s experience

Melissa Harris-Perry, host of the much-loved Melissa Harris-Perry Show on MSNBC, has recently ended a struggle for editorial control with the network by deciding to leave her show. In a publicly-published email to her staff, she said:

“MSNBC would like me to appear for four inconsequential hours to read news that they deem relevant without returning to our team any of the editorial control and authority that makes MHP Show distinctive. I will not be used as a tool for their purposes. I am not a token, mammy, or little brown bobble head. While MSNBC may believe that I am worthless, I know better. I know who I am. I know why MHP Show is unique and valuable. I will not sell short myself or this show. I am not hungry for empty airtime. I care only about substantive, meaningful, and autonomous work. When we can do that, I will return–not a moment earlier.”

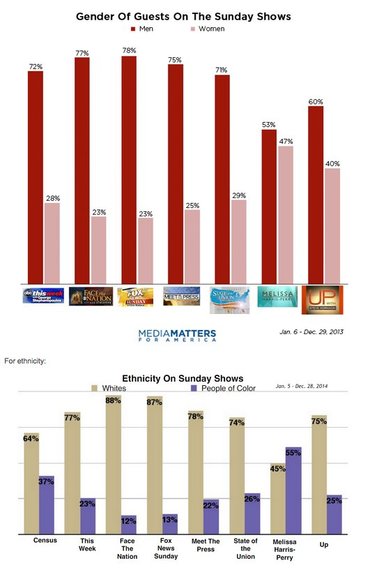

Melissa Harris-Perry has a PhD in political science and taught American voting and elections at some of the country’s top universities including Princeton, the University of Chicago, and Wake Forest. An expert in her field, she consistently brought diverse voices to her show to talk about elections, local and national government, and social movements. The MHP Show was vastly more diverse than any other Sunday cable news show. Her guests were 45 percent white, compared to a 75-88 percent range from all the other major political weekend shows. Hers was also the only show that came anywhere near a 50-50 gender balance.

After years of fighting for editorial control, MHP reached her limit when MSNBC’s white male leadership told her she could not discuss Beyonce’s Formation video, even though it is politically relevant and the entire country was talking about it. They wanted her to stick to election politics instead. What happened was MHP spoke about Formation anyway, as footage of Jeb Bush and Chris Christie rallies in New Hampshire appeared in a box on the screen. MSNBC was not pleased.

If you watch MHP’s commentary on Formation, the subtext is loud and clear. She says:

“Beyonce is making an artistic statement that is boldly, unapologetically, black. She’s giving us black bodies and a black politics that will not be silenced or ashamed, but instead commands space for the one thing the video tells us they are most definitely here to do – as Beyonce says in the song’s refrain -‘I slay’.”

Melissa Harris-Perry is telling MSNBC that she too is bold, unapologetic, and came to slay. She will accept nothing less than full respect for her leadership and editorial vision – and this vision is fully linked to her identity as a black woman. She then informed MSNBC that she’s leaving.

The network responded to her publicly-shared email by saying “She’s a brilliant, intelligent but challenging and unpredictable personality” and “It’s highly unlikely she will continue” at MSNBC. Her email “is destructive to our relationship.”

MSNBC trying to slam MHP by using “challenging” and “unpredictable” as coded language both for “a confident woman who will not stay in her lane” and “a black person who doesn’t care what white people think.” Not only is MHP supposed to experience self-doubt as a woman, but MSNBC is shocked that she expresses such confidence as a minority in an overwhelmingly white-dominated industry, operating within a system of white supremacy. They view her confidence as an act of extreme audacity. Once again, we’re seeing the kind of words that could easily appear in any successful woman’s performance review.

MSNBC’s statement also misleadingly makes it sound like there’s still a relationship that MHP is recklessly damaging. Newsflash: you can’t fire someone who already quit. The email can’t possibly be “destructive to the relationship” because MHP already decided that there is no more relationship.

The network is treating MHP like she should have imposter syndrome, but she doesn’t. She is completely aware of her contribution and self worth, and she made the decision to leave on her own terms. Unsurprisingly, media reporting echoed MSNBC’s incredulity, saying that the network “severed ties with her” or “fired her” or even that she “went on strike.” It’s so hard for people to grasp that MHP simply took the power in this situation, and left.

The best part of this story is that not only did MHP choose freedom over silence by leaving MSNBC, but she also did it by refusing to sign a non-disparagement clause on her way out. The network assumed she would exchange her silence for cash in their exit negotiations, but she didn’t. And then she simply carried on speaking truth:

So #MSNBC y’all keep making cable great again. I’ll be staying challenging & unpredictable. #NerdlandForever pic.twitter.com/BCDOBLfITm

— Melissa Harris-Perry (@MHarrisPerry) March 1, 2016

MSNBC tried to publicly punish MHP for her confidence, but she’s refusing to be silently “disappeared” like former hosts. The network and the media can still try to spin her story however they want, but she won’t be enduring it silently, and that will make things a lot harder for them. Not only do they have to field questions about her departure, but also the wider issue of their participation in the whitewashing of cable news.

MHP and HRC are fighting different battles, but both of their stories reveal the pushback that happens when persistent confidence flies in the face of competence bias.

Since it just wouldn’t be fair to talk about half the population being taught to self-doubt, without talking about the other half being taught to self-aggrandize, let’s move on to entitlement syndrome.

Entitlement syndrome

Entitlement syndrome is formally known as the Dunning-Kruger effect or illusory superiority. It disproportionately affects white men (whiteness and maleness being powerful intersecting privileges), and usually remains invisible and undiagnosed. Here’s a quick definition:

Entitlement syndrome is when a person (usually a white man) overestimates his own skills, relative to others. He believes he deserves not only respect for his accomplishments (no matter how mediocre) but also success. He doesn’t have to go above and beyond to qualify for excellence, and if he doesn’t get the success he deserves, it’s not his fault. He can use vocal fry, upspeak, and “sorry” and “just” because he expects to be judged solely on the content of his speech. He also believes he deserves the benefit of the doubt at all times, a partner who is much more attractive than him, and copious amounts of public space.

Both entitlement syndrome and imposter syndrome have their root in the unconscious competence bias that operates at every level. You can see it clearly when you look at how men and women view success and failure.

When women succeed, they tend to attribute their success to external factors (imposter syndrome). But when men succeed, they tend to attribute their successes to inner qualities like dedication and talent (entitlement syndrome). When men and women fail, the attributions get flipped. Women tend to blame their failures on internal shortcomings or a lack of effort (imposter syndrome), while men tend to blame circumstances outside their control (entitlement syndrome). So in a general sense, we have men internalizing mostly successes and women internalizing mostly failures, an internal thought process which is then strongly reinforced by outside forces.

Entitlement syndrome is like being coated in confidence (and competence!) teflon. You expect to succeed, and this is reinforced by external circumstances: those around you also expect you to succeed. Even if you’re less qualified than other candidates, you believe in yourself. Your competence is rarely questioned by others, so why would you question it? When the competence of other candidates – women, people of color – is rigorously vetted, you also don’t question it. Entitlement syndrome is why we so often see white male mediocrity promoted over more qualified candidates who are not white men.

Entitlement syndrome never makes the self-help circuit. Unlike imposter syndrome, nobody’s making any money off pathologizing a destructive thought pattern that disproportionately affects privileged white men – because for them, it’s not a problem. It’s great. The entitlement syndrome thought pattern is allowed to exist invisibly as the status quo to which other groups must conform in order to be successful. If a group is having trouble, the message is that they need to fix themselves. The system is fine, they just need to work harder to fit into it.

Except the system is not fine. It’s broken. Now what?

Entitlement syndrome is a characteristic of a group that expects to fit easily into an environment that was designed especially for them. Imposter syndrome, on the other hand, is the cognitive dissonance that happens when a group does everything “right” to fit in and succeed, and yet can’t escape a situation in which their competence is regularly under fire. The examples of Melissa Harris-Perry and Hillary Clinton show that biased attacks on competence only increase in intensity the more competence and confidence a woman demonstrates.

The problem is systemic and environmental, so the solution also must also be systemic and environmental. As scholar Karen Ashcraft states, “social change is about fixing environments, not people.” Here are a few examples of things we can do:

- If your company is holding assertiveness trainings for women, ask what trainings will be held for men. If only the women in a workplace are deemed in need of special training, it sends a message that the men’s skill set is the standard. The reality is that everyone can benefit from dexterity in communication.

- Through unconscious bias training, cultivate “privilege traitors” who do the work of debunking their own privilege and pointing out unconscious bias when they see it.

- Keep an eye out for backlash that happens when a woman asserts confidence in the workplace. If you are involved in a performance review process and a word like “abrasive” comes up, push back. Explain why that word is problematic, and stick to specific, performance-related examples.

- If you’re in a meeting and you witness a woman being interrupted by a man, who then essentially repeats what the woman just said, expecting (and somehow getting) credit for it, cut in as soon as they take a breath. Redirect attention back to the woman by saying something like “Oh, that’s like Lila was just saying about ____. Lila, tell us more about how ____ would work.”

To really get at the root of competence bias, we’re going to have to arrive at an environment where no one group is seen as the yardstick for competence. Per Ashcraft, we need to create environments where difference can emerge and flourish. This means dropping any assumptions of what difference will look like. Instead of saying, “we need more women in politics because they’re great at building consensus” or “we need more women of color hosting cable news shows because they’re better at bringing in more diverse guests” we should be saying “we need more diverse representation in politics and cable news because it reflects the plurality we live in.” We can’t rely on tired stereotypes to assume what impact this will have. We can only encourage humility, curiosity, and openness around how that difference will emerge and what it will look like.